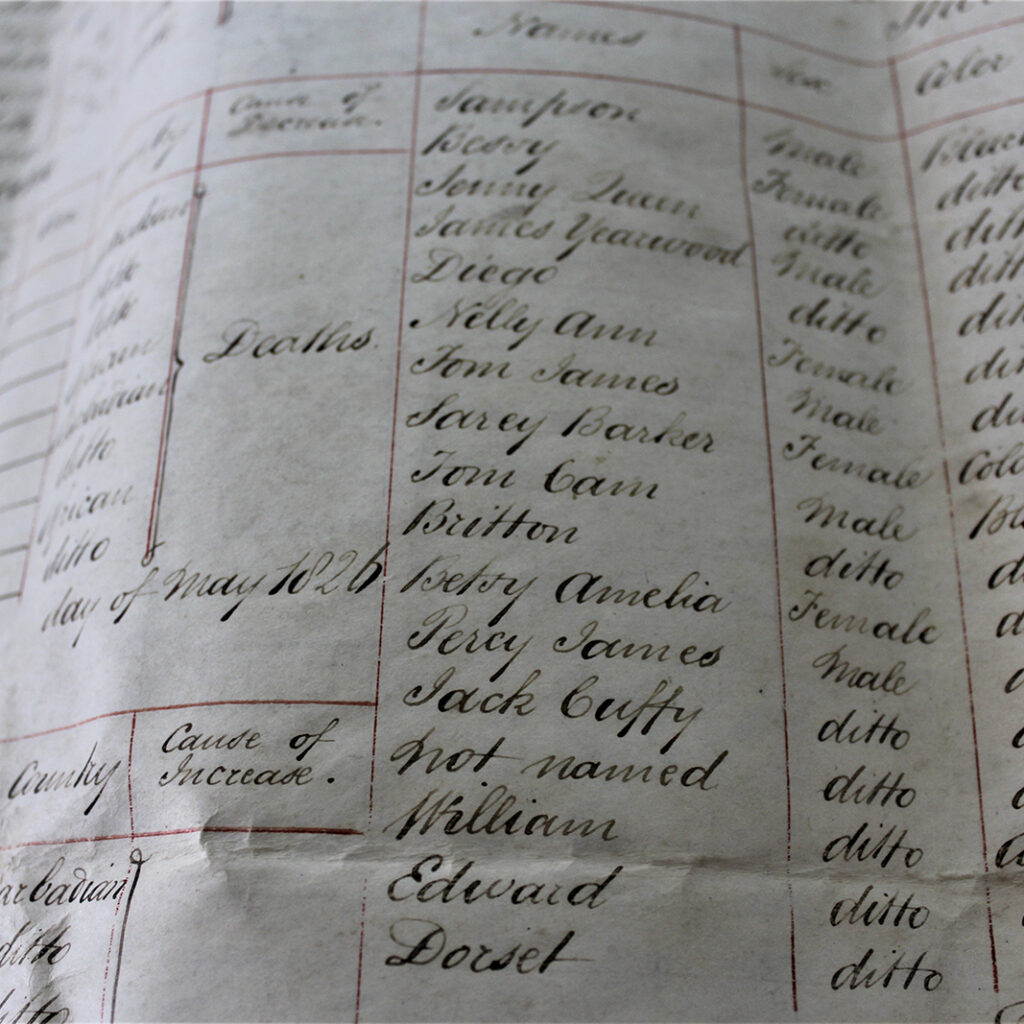

Several members of the Holburne family had careers in the British Navy. William’s grandfather, Sir Francis Holburne (1704–1771), became Rear Admiral of Great Britain in 1770. William joined at the age of 11 and his career took him to the Caribbean and Brazil. He also embarked on ‘Grand Tours’ of Europe in the 1820s. By this time, the British Empire had expanded and the nation’s wealth had been accumulating through enslaved labour in overseas plantations and trade with Britain’s colonies.

The Holburne Family and Caribbean Plantations

This display shows how the Holburne family were connected to plantations in the Caribbean through their naval links and marriage into plantation-owning families, particularly the Balls, Lascelles and Cussans families. Through these interests and connections, the Holburnes of Menstrie are an example of the British elite who derived a large part of their wealth from Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade in the Caribbean.

Many others in the South West region amassed wealth from Caribbean plantations, some of whom were actively pro-slavery and opposed its abolition. These included the Pulteneys of Bath; William Beckford of Bath; the Blathwayts at Dyrham Park; and Edward Colston, John Pinney and Thomas Farr in Bristol.

BARBADOS

The first colonies of the British Empire were founded in North America (Virginia, 1607) and the West Indies (Barbados from 1625, and Jamaica from 1655). The British supplied, traded and transported African people to work in the plantations in their colonies. In the late eighteenth century, Britain succeeded Portugal and Spain as the most prolific slave-trading European nation. Sugar amounted to 93% of exports from Barbados during this period.

William Holburne’s grandmother, Frances Ball (c.1717/18–1761), was born in Barbados. She was the daughter of Guy Ball (c.1686–after 1722) whose family had taken ownership of the Williams Plantation, Christ Church, by the 1720s.

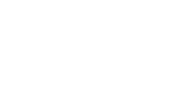

The Plantation Day Book on display here is from 1722, when the Balls had ownership.

Frances’ first marriage, in 1732, was to Edward Lascelles (1702–1747), a plantation owner and Collector of Customs in Barbados.

The Lascelles family were sugar factors, securing interests in Caribbean islands as early as 1648. In addition to money-lending to slave-traders, Edward and his brother, Henry, are reported to have also kept some of the sugar duty they collected for themselves, making their presence in the Caribbean a significantly profitable one.

Frances’ and Edward’s son, also Edward (1740–1820), became the 1st Earl of Harewood and inherited from his cousin Harewood House, Yorkshire, which William Holburne visited as a child. Some of the Lascelles family were members of the British parliament, and some held a strong pro-slavery stance.

By 1787, the Lascelles held more than 27,000 acres in the Caribbean and owned almost 3,000 enslaved people.

Following her first husband’s death in 1747, Frances married Admiral Sir Francis Holburne in Barbados.

ANTIGUA

As tastes and demand for sugar grew in British society, so did the need for labour and the number of people being enslaved to work in the Caribbean plantations increased greatly. By 1750, sugar was the most valuable commodity in European trade, making up a fifth of all imports. Today, the sugar mills of Antigua are a popular tourist attraction.

Admiral Sir Francis Holburne, William Holburne’s grandfather, who also served as an MP, was stationed at English Harbour, Antigua, from 1743, becoming Commander-in-Chief of the ‘Barbadoes and Leeward Islands’ Station in around 1748.

Such stations were set up across the Caribbean by the Royal Navy to protect the ownership and expansion of Britain’s hold over the sugar-producing islands and their ship convoys.

Edward Lascelles had also been a contractor in Antigua, and with his brother, Henry, held working relationships with the station captains. Admiral Holburne likely interacted with the Lascelles family prior to his marriage to Frances.

JAMAICA

80–90% of the sugar consumed in Western Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries came from Caribbean plantations and was made available in Britain as a direct result of the colonial practice of enslavement. By 1800, the number of people enslaved in Jamaica was over 300,000. It has been estimated that, overall, about 12 million Africans were captured, enslaved, and taken to the ‘Americas’ during Britain’s colonial history.

Sir William’s main source of income was from an annuity of £500 a year from his aunt, Catherine Cussans (1753–1834).

Catherine was the daughter of Admiral Sir Francis and Frances Holburne, and sister of Sir Francis Holburne (1752–1820), William’s father. She married Thomas Cussans II of Mayfair (1737–1796) in 1775.

Thomas was born in Jamaica and his wealth derived from there, notably the Winchester and Hope Pen Plantations.

Catherine’s income came partly from her marriage, her own savings from shares in companies such as the West India Dock Company, and from the Ball family estate after Frances, her mother, died.

The Ball family also had interests in Jamaican plantations, namely: Airy Mount, Chancellor’s Hall, Prospect and Top Hill, and members of the Lascelles family were Trustees of Catherine’s estate.

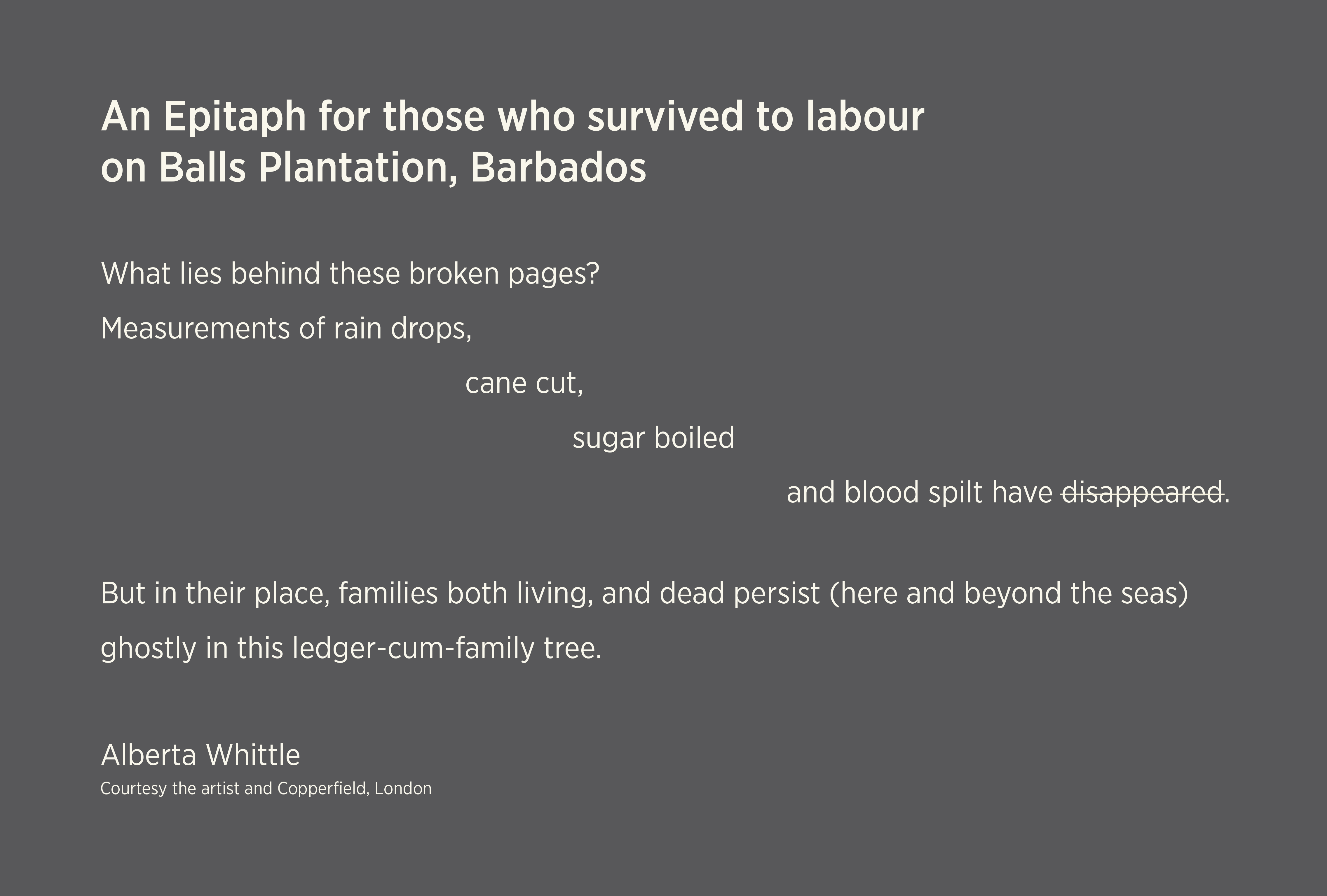

THE PLANTATION DAY BOOK

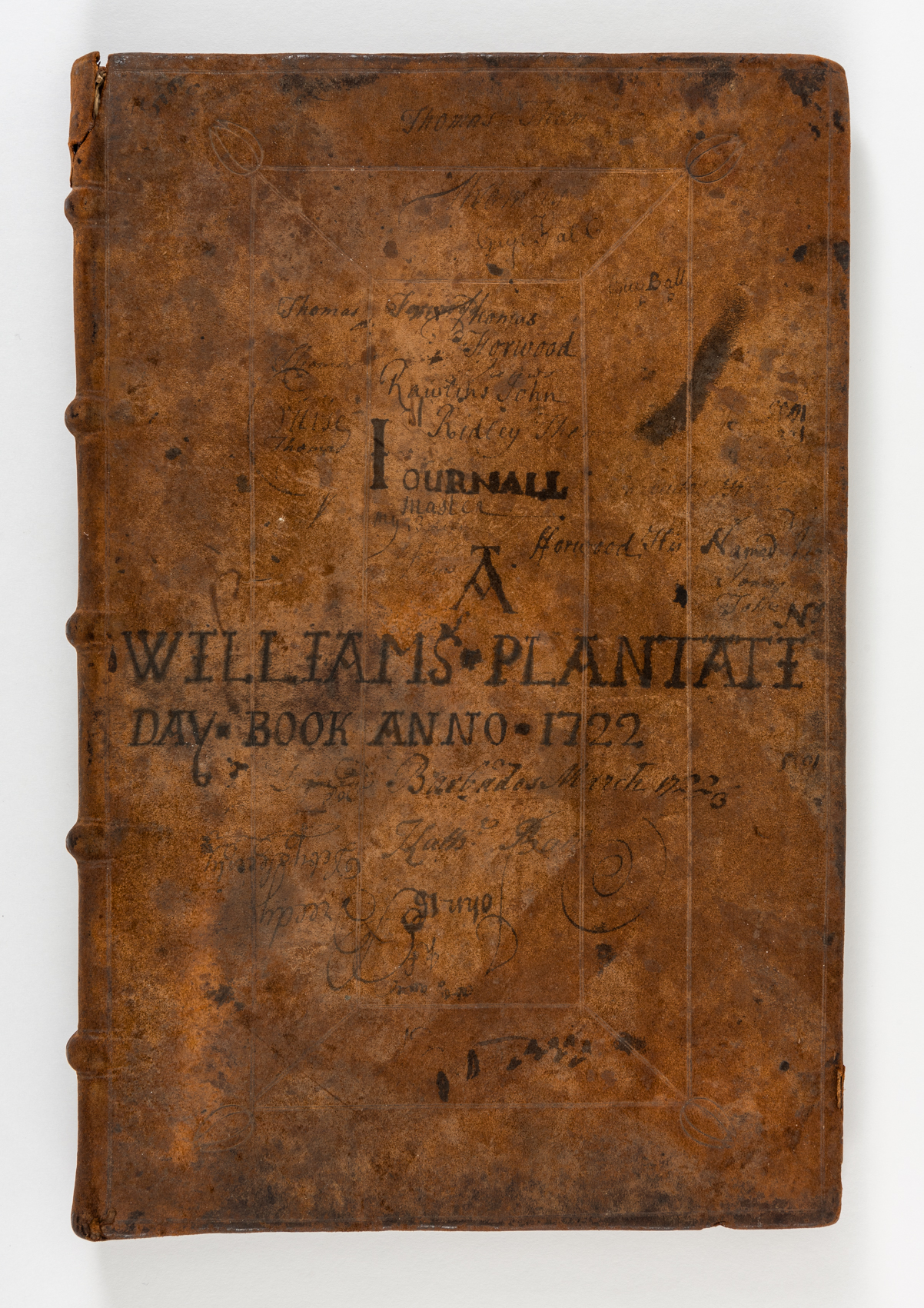

This Day Book originates from the plantation in Barbados which belonged to William Holburne’s great-grandfather, Guy Ball. Ledgers like this were used to document imports and exports, and often included the names of enslaved people who were born, bought, sold, or died on the plantation.

In contemporary research, archival materials like this can assist in unearthing the agency and lived experiences of enslaved people, and are significant for black Barbadians wishing to research family histories, as very little documentation exists elsewhere.

An unusual feature of this book is that the majority of its pages have been cut out. When, why, and by whom remain unanswered questions. Only one page with legible content remains and denotes a delivery of ‘provisions’ of candles, beef and cocoa; the name ‘Warrener’ is seen as the receiver of these goods. Records show that Guy Ball sold 25 acres of land to William Warrener, another planter in Christ Church, Barbados, in 1720.

The first record of Ball’s plantation site was in 1671 in the will of Captain John Williams. By 1680 it was 469 acres and it was later acquired by the Ball family. Dated 1722, the Plantation Book features the name Williams on the cover, along with additional inscriptions, most likely of others connected to the estate at one time or another. ‘Guy Ball’ appears twice, ‘Thomas’ appears several times, and the name ‘John Breedy’ can be seen upside-down.

The book highlights the transactional treatment of people of colour through the colonial practices of the British Empire, and the origins of the consumption and luxury in this gallery, which warrants acknowledgement and remembrance.

Original Deed of Mortgage and schedule of Ball Plantation in the island of Barbados received 1 August 1834 and dated 29 July 1834 including the names of enslaved people as part of the documentation of ownership.

A few of the names of enslaved people included in the mortgage deed

Sally

Rose

Mary

Jack

Percy

William

Sammy

James

Ned

Yearwood

Diego

Dorset

William

Infant

Jonny

Sampson

Bessy

Nelly

Anti-Slavery and Colonial Resistance in Bath and Somerset

While many in Bath and Somerset in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries profited from the labour of enslaved people, others actively opposed the slave trade. Some are recorded here alongside others who, rejecting racial discrimination through their work, demonstrated black agency. This multiracial cohort of men and women came together across social, global, and physical barriers to disrupt and condemn colonialism’s racist, violent and dehumanising practices. The legacy of colonialism continued into the twentieth century and its lasting impact is experienced in the present day.

Watershed map of England & Wales. No. 5. Letts’s popular atlas. Letts, Son & Co. Limited, London. (1883) courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

People confined to plantations in the Caribbean consistently revolted against enslavement. Many Quakers questioned the morality of colonial practices and actively campaigned against all forms of slavery. In Britain, these included Granville Sharp (1735–1813), Joseph Sturge (1793–1859), Hannah More (1745–1833) of Bristol, and William Wilberforce (1759–1833),

a frequent visitor to Bath.

Despite strong opposition from slave traders, sugar factors, and plantation beneficiaries, campaigns against the trade led to the establishment of Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act in 1807.

Slavery was not immediately halted, however. Enslaved people in the British Caribbean were not legally emancipated until 1834, with many forced to complete an imposed term or further displaced to British colonies. Slave-owners were compensated financially for the loss of workers and labour was replaced by the indentured servitude of Indians, transported to the Caribbean by the British from 1838.

Charles Ignatius Sancho

(1729–1780)

African-British literary, political and cultural figure

‘Ignatius’ was born on a ship in transit from West Africa to the Caribbean in 1729, and orphaned at the age of two. After being ‘gifted’ to a family in Greenwich as their slave, Ignatius escaped and developed his literary skills whilst serving under the House of Montagu, a noble family originating in Somerset. He wrote essays, compositions and plays, eventually owning a shop in Mayfair, and, in 1768, he was painted by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) while in Bath. An active abolitionist and campaigner for social reform, Ignatius was the first recorded African to vote in Britain in 1774.

Josiah Wedgwood

(1730–1795)

English potter, manufacturer and abolitionist

Josiah founded his pottery company in Staffordshire in 1759. Led by a hugely successful tastemaker, Wedgwood pottery was exported widely to Europe and, from 1774, he had a showroom in Milsom Street, Bath. He joined the committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and, from 1787, the Wedgwood company mass- produced a cameo medallion bearing the words,

‘Am I not a Man and a Brother?’ as a symbol of the anti-slavery movement. Yet, the design depicted a black, enslaved man kneeling, portraying him in a vulnerable and passive position rather than one of equality, demonstrating that these medallions were produced in a highly racialised social context.

George Polgreen Bridgetower

(1779–1860)

African-Caribbean & Polish composer and violin virtuoso

George was born in Poland to a Barbadian man and Austrian-German woman. The name ‘Bridgetower’ is thought to derive from Bridgetown in Barbados. George studied violin at an early age and became fluent in several languages, advanced by opportunities that came from his father serving a Hungarian prince. In 1789, at the age of 10, George performed for royalty at Windsor, England. He then played at Bath Assembly Rooms, attended by King George III, and at two more sold-out performances in Bath that December. Growing in popularity in Europe, he met Beethoven in Vienna in 1803, who composed a sonata for him. They first performed it together; however, following a disagreement, ‘Violin Sonata No. 9’ was dedicated to another violinist. Though some newspaper reports of the time praised George’s talents, others described him as a credit to the ‘mulatto’ race – a prejudiced statement today.

Ira Alridge

(1807–1867)

African-American actor, playwright and theatre manager

Ira was born in 1807 in New York, where he developed an interest in the theatre. He faced extreme difficulties as a black actor in America, and due to the racism he experienced, left for England in 1824 to pursue his career. Arriving at the age of seventeen, a year later, he had debuted on the London stage. Despite continued prejudice, Ira performed across the UK and his portrayals and adaptations of Shakespearian roles earned him a popular reputation as an actor in nineteenth- century Britain. Subsequent tours took him to

Europe and Russia. Ira became manager at the Coventry Theatre in 1828, and starred in Othello and The Padlock at the Theatre Royal in Bath in 1832. Ira’s career developed amidst mounting debate in Britain around the continued practice of enslavement and the treatment of those impacted by it.

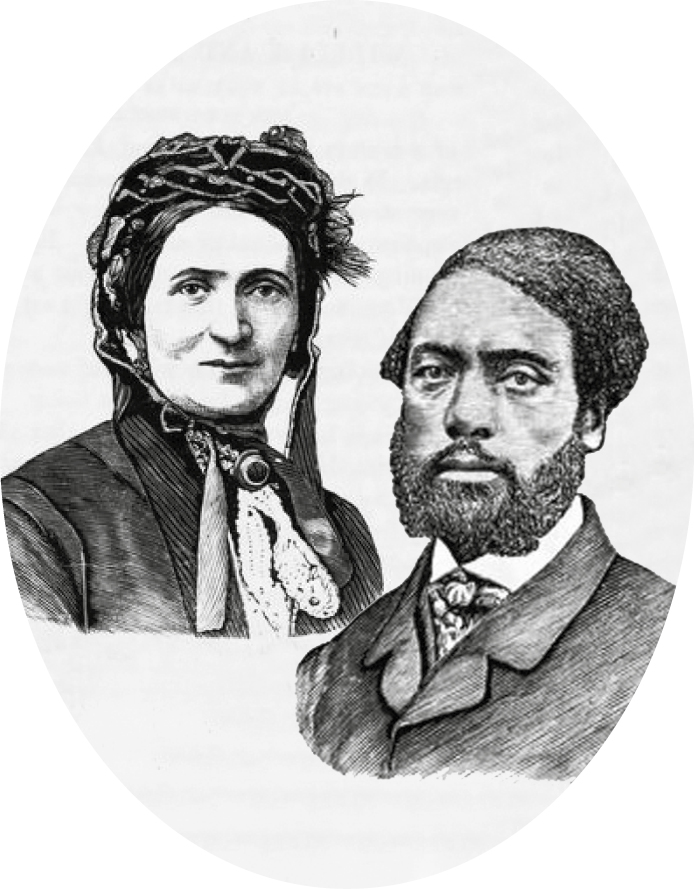

Ellen Craft (1826–1891) and

William Craft (1824–1900)

USA plantation escapees, anti-slavery authors and freedom speakers

Ellen and her husband William were an enslaved couple on a plantation in Georgia, USA. Together, in 1848, they fled their bondage. As a teenager, William’s family had been separated and sent to various plantations in the USA. Ellen’s mother had been a slave in her father’s possession. Reportedly, Ellen’s facial resemblance to her father, and her light skin-tone, aided their escape. She had learnt to sew as a house servant and knew how to make men’s clothing. Crossing gender and racial barriers, Ellen passed as a white male slaveholder accompanied by her black valet, William. She feigned mouth and arm injuries to avoid speaking and writing. They arrived in Britain in 1850, joining reformist organisations and speaking publicly about their plight. In 1851 they travelled to the South West and spoke in Bath. Their experiences were published in 1860: Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom: Or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery.

Catherine Impey

(1847–1923)

English Quaker, anti-racism activist and publisher from Somerset

Catherine was a Quaker from Street, Somerset. In 1888, she founded Anti-Caste, Britain’s first anti- slavery publication. The magazine raised concerns about the British Empire’s racism and supported unity across races and descent, encouraging black writers to use it as a platform. The Quakers were sympathetic to the rights of women, believing in simplicity, truth, equality, and community, and helped to progress women’s rights in the USA. Hosting other anti-slavery activists and visitors from overseas at her home, Askew House, Catherine envisioned an anti-racist ‘international society’. Catherine was a keen vegetarian and remained child-free and unmarried.

Ida Wells

(1862–1931)

African-American feminist, writer and anti-lynching campaigner

Ida was born in 1862 in Mississippi, USA, where her parents had been enslaved. Having been ‘freed’ during the American Civil War (1861–1865), she began campaigning against racial discrimination and, as a teacher, protested against the racial pay gap in education. Ida travelled across the USA and Britain, speaking out against racial violence and in support of women’s suffrage. Invited to Britain by Catherine Impey in 1893, Ida visited her in Street and subsequently contributed to the Anti-Caste journal. She founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. A feminist who fought for African-American rights, Ida is most remembered for her defiant campaigning in the late nineteenth century to end America’s lynching practices of black people.

Lady Kathleen Simon

(1869–1955)

Irish anti-slavery speaker and author

Kathleen was born in Ireland and witnessed racial discrimination whilst residing in the USA in the late nineteenth century. This inspired her life-long engagement with anti-racism campaigning in the years after Caribbean emancipation. Kathleen published Slavery in 1929, which described the conditions of slavery and enduring practices of racial discrimination across the world. She regularly corresponded with the African-American sociologist and author, W. E. B. Du Bois, and greatly admired his work. In her letter to him of 1929, where she asked him to review her book, she urged him to encourage “his people” to prosecute English hotels who were opting to “exclude the coloured people”, infringing their legal rights. In 1930, Kathleen spoke for the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society in the Guildhall, Bath, where she unveiled William Wilberforce’s plaque at 36 Great Pulteney Street.

Dr Harold Moody

(1882–1947)

Jamaican scientist who founded Britain’s first civil rights movement

Harold was born in Jamaica in the post- emancipation decades. He came to Britain in 1904 to study medicine in London, where he set up his practice. Providing support for people marginalised in British society, Harold became a racial equality campaigner and was a founding member of the UK’s first civil rights organisation, the League of Coloured Peoples, in 1931. A high-achieving academic and respected physician, Harold spoke in Bath in 1946 at the Over Twenty Club at Argyle Congregational Church. Here he shared his research into hematological (blood) identity markers in black and white men. His results showed there was no scientific evidence to support the constructed colour bar that was in place, under the falsity of which he had been refused work during his own life.

Films

Listen to the Curator of the redisplay, Jill Sutherland, and young people talking about their responses to the Plantation Day Book and exhibition.

If you have enjoyed this online exhibition please help us to continue to reach wider audiences by making a donation.

With support from

Devised by Jill Sutherland, Artisa Foundation Curatorial Fellow, 2021.

Image credits: Ignatius Sancho (detail) by Francesco Bartolozzi (1728–1815), after Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), stipple engraving and etching, 1802, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Josiah Wedgwood (detail) by George Salisbury Shury (1815–1894), after Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), mezzotint and etching, 1863, courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington; George Polgreen Bridgetower (detail) by Henry Edridge (1768–1821), graphite with watercolour, 1769–1821, The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo; Ira Aldridge (detail) by unknown artist, albumen silver print, c.1865, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Ellen Craft and William Craft (detail) by unknown artist, engraving, 1872, from The New York Public Library; Catherine Impey (detail) by Eve Campion-Dye, 2021; Ida Wells by unknown artist, engraving, c.1894, from The New York Public Library; Lady Kathleen Simon (detail) by Bassano Ltd., whole-plate glass negative, 1920, Historic Images / Alamy Stock Photo; Dr Harold Moody (detail) by Eve Campion-Dye, 2021